It’s a hot and sunny day, and I’m melting. I’m wearing a quilted racing suit, gloves and helmet and I’ve been wedged into the cramped passenger seat of one of the most claustrophobic cars I’ve ever sat in. I’m inches above the road, surrounded by bare aluminium and carbon fibre, and the driver is shouting something I can’t hear over the chainsaw racket of the rear-mounted engine. And we’re travelling – well, not very fast at all. Maybe 20mph.

Welcome to the weird world of Shell’s Eco-marathon, an annual competition to see who can travel the furthest on a single litre of fuel. And strapped into my five-point harness I can’t help reflecting that I’m sat in the most comfortable class of car in the competition, known as an Urban Concept and designed to vaguely relate to road legal reality. Most teams compete instead in the Prototype category, where the “cars” resemble streamlined coffins, as low to the ground as a spaniel’s ears. I can’t imagine what it’s like to lie in one of those and try to compete.

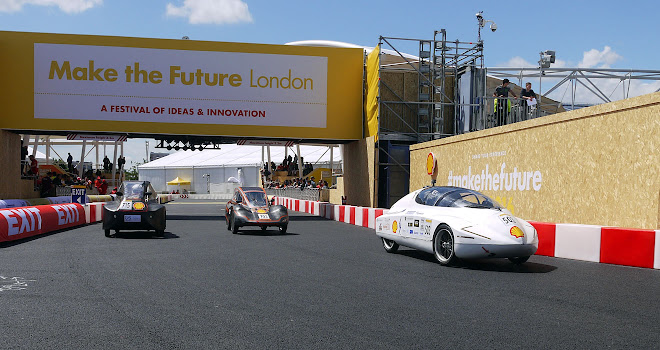

The European leg of the marathon has arrived in London this year, where a 1.4-mile course has been laid out amid the greenery of the Olympic Park. Cars complete eight-lap stints, with the Urban cars having to draw to an enforced stop and set off again as they reach the start-finish line on each lap. Consumption is calculated by how much fuel remains when the cars pull into the paddock.

Using power throughout each lap is a waste, of course, so thankfully the booming engine in my car is frequently switched off. But there’s a limit to how much you can coast. For laps to qualify, cars have to meet a minimum average speed of 15mph, so judging when to switch on or off is an art (and possibly a science, given that many of the 200 teams have employed computer modelling to prepare for the race).

My car is powered by a 125cc Yamaha scooter engine and is good for about 500mpg, I’m told. There’s not much suspension travel and the course is a bit lumpy. My driver, Shell’s Ian Moore, tells me that some of the more fragile cars haven’t survived first contact with the bigger bumps. In a cruel blow, there’s a speed hump at the foot of the route’s major incline. Denied a run up, a few of the weedier vehicles are struggling with the climb – we pass two stranded Prototypes on our way to the top of the crest.

The car I’m in weighs just 255kg, marginally over the weight limit for the actual event. It’s a demonstrator vehicle that Shell is running to give visitors like me a taste of the track. It used to be light enough to compete but has gained a few pounds to become fully road legal – only some last minute hiccup with the DVLA prevented it wearing its number plates with pride.

The actual competitor cars are designed and built by students from around the world – there are no works teams, though most cars are sponsored and a handful look so beautifully put together they must have cost a fortune. One of the leading cars has a teardrop carbon fibre monocoque that weighs just 23kg. Another has carbon wheels that are less heavy than the tyres.

In all, 29 nations are represented, not all of them European. A car that resembles a salvaged garden shed has come from Indonesia, there’s an amazing 3D-printed car from Singapore, and I spotted stars and stripes on the back of one low-slung racer.

As well as the two varieties of Urban and Prototype cars, there are numerous fuel classes: petrol, battery, diesel, natural gas, hydrogen, and alternative fuels such as ethanol are all represented.

Having been shoehorned out of the demonstrator, I’m guided around the paddock by Damien Hallez of tyre maker Michelin. The company makes a selection of tyres specifically for the Eco-marathon, and he’s keen to point out how many of the cars are using them. Those that aren’t doing so are generally running on skinny bicycle tyres.

Hallez explains that the challenge for his firm is to produce tyres with the minimum rolling resistance, a factor that’s measured in kilos per tonne – that’s the forward force in kg needed to make the tyre roll for every tonne of weight supported by its contact patch. None of the cars weigh anything like a tonne, so the motive force needed is measured in grams.

Ordinary car tyres need to drop below 6.5kg/tonne to score an A-rating for rolling resistance, under the standard European labelling scheme. Michelin’s Energy Saver Plus road tyre comes in at about 6.2kg/tonne, Hallez says, while tyres produced for the Urban Concept class achieve 1.3kg/tonne and Prototype tyres just 1.1kg/tonne.

Rolling resistance is caused by the way the tyre squashes where it meets the ground, creating the oval contact patch that offers grip. As the wheel rolls onward each part of the tyre is repeatedly squashed and released. This kneading effect warms the tyre up, creating the energy drag felt as friction. Small movements of the tread blocks contribute to the same effect.

I can’t help noticing, as Hallez explains the science, that some of the teams are running his tyres with a narrow bald stripe down the middle. Pumping the tyres up well beyond their rated pressure tends to minimise the contact patch, reduces the amount of squashing and quickly wears away any troublesome tread blocks. I’d be prepared to bet that some of the teams are running tyres with considerably less than 1kg/tonne resistance.

But as Hallez explains, there is always a trade off. “Grip and rolling resistance are opposing challenges,” he says, “the same goes for wet grip versus dry grip, or tyre longevity and fuel efficiency.”

Progress in the science of rubber compounds will improve matters over time, as does the trend towards “slimline” profiles: big diameter wheels with narrow tyres, as seen on the BMW i3 electric car, are more efficient. “That’s the shape of the future,” says Hallez.

I’m not sure if the cars lapping the London circuit are exactly the shape of the future. Most people want something bigger and more robust and less like a coffin – though I suppose the Volkswagen XL1 shows that similar thinking could feasibly reach the road.

Mind you, the winning petrol-powered Urban Concept, number 502 entered by French team Lycée Louis Delage, achieved 446km/litre, or about 1,260mpg. How does London to Edinburgh for £1.50 sound? For that kind of economy, I’d be prepared to live with a little discomfort.